Request Information

Ready to find out what MSU Denver can do for you? We’ve got you covered.

Join us in getting to know our faculty and staff through this relay interview series where the person being interviewed gets to choose and interview the next interviewee. The interview questions and format are also chosen by each interviewer for diversity.

ANNE: What kind of creative play/work did you do as a child?

WALTER: I did a lot of stuff. I did a lot of exploring in Fountain, CO. We lived on the edge of development. I always thought there was a mysterious place or a grotto or something to find. If there was an irrigation canal, we might get a tube and go on down it. If there was a group of trees… I’d think, “Oh, there has to be something over there.”

ANNE: Can you describe your journey as a thinker/maker/creator?

WALTER: I’ve always had it. My dad always seemed to have a lot of these skills and my mom trained herself to be a machinist. We did stuff around the house. Growing up where I did, everyone was very vocational… welding, building. That was what I grew up around. You did it yourself, but if you couldn’t do it yourself, you knew someone who could. I always had that trait in me.

My wife and I moved into an old house and I was a stay-at-home dad and fixer-upper. I started getting into blacksmithing. When I was a kid, there were farmers around us that did blacksmithing. They’d say, “Hey kid, I want to show you something. Make one of these. Try it again. Make another.” So, as an adult, I started doing blacksmithing at my house and the more I did it, I got more tools and learned more.

We started reading The Hobbit with our kids, so I was creating all these metal armor and swords for them and researching. There was a point when I said “I’m doing all this research, so…” And my wife said “You should go to school to study archeology.” I went to CU’s Anthropology Department that had an emphasis in archeology. All the archeology classes were graduate level and at some point, I was getting a little tired of it. But by then my advisor told me that I only had 6 more credits to finish a degree in Anthropology. So, I just did that and got an Anthropology degree.

As I was still working in metal, I felt like I needed someone to critique what was doing. So, I took sculpture classes at CU. Sculpture was pretty straightforward. That was an epiphany to me… that what I was doing was art and not only craft. I graduated with a degree in Anthropology. I also took some metals and jewelry classes at MSU when they had pooled classes with CU. I had MSU instructors, Anne Hallam and Yuko Yagisawa for those. I have two degrees, one in Anthropology and then I did one in Sculpture as well.

ANNE: What is your job at MSU and why does it seem like a good fit for you? (I’m just assuming you think that, but maybe you don’t!)

WALTER: Basically, I’m the studio manager for CU and MSU Denver. It seems like a really good fit for me, because when I was going to school here, I was a monitor. I came with a whole set of skills when I started here. I was teaching other students after hours. Professors would tell students to come in on the weekend when I was working. As a work-study, I did more than the job description. Without having a way to title it, I was almost an assistant. Coming back now, it’s kind of doing that again.

ANNE: Why do you make things by hand?

WALTER: I guess I’m really intrigued with craft and doing things yourself. A lot of things. When I was younger, I couldn’t afford certain things, so I made them. When you make it yourself, you can control the quality of it and you can make it your own.

ANNE: How do you think about traditional craft and its intersection with fine art?

WALTER: I think that craft should be a bigger part than it really is. Some people (like blacksmiths) might see their craft as making a functional thing for someone else. In this sense, art is functionally useless. Art is so nebulous to that person who crafts something, even though they do have a thought behind what they are making and a feeling behind it. Taking a craft and being able to work it, you are able to understand it and you can process the formal side of fine art into the craft. So, I consider art and craft almost the same.

ANNE: How can art students who work with physical objects contribute to society in a world that is becoming more and more virtual?

WALTER: In a way I’m torn on that. I think that without some connection with the past… the beginnings of something… without any way to have reference to what came before something, we can’t really see where it can go. My art always is about humans. How we think… what we do. It’s purely anthropological. When I see a flint tool, I think of the thoughts, the emotions, and the creativity that went into making it. Humans are amazing in good ways and a lot of bad ways. If we move from some of these traditional crafts, we lose some of the creativity we have as a people. Culture and society changes over time and so many people don’t know what came before.

ANNE: Yea and even more recent past, like not knowing who made the clothes we have on.

WALTER: I’m also a master weaver.

ANNE: What?!!!

WALTER: I was just doing weaving at home. Denver used to offer classes in traditional skill sets in a middle school near where I lived. They got rid of the program, but the instructor asked if I wanted to continue. She set up a classroom through Colorado Free University. I was the only male in the class. It was so funny. My son was born during that time. They threw me a baby shower. I brought him to the class and set him up in a little corner where he played. This is thanks to my mom. She would tell me, “There are no man jobs or woman jobs.”

ANNE: What do you think about plastic? (Ok that’s a weird question, but it is kind of the elephant in the room when it comes to our physical reality these days.)

WALTER: I definitely have a problem with plastic trash in our oceans. We need to figure out a way to recycle it and make less of it. I would be willing to work with it. Wait… actually I have been working with it! I’m doing some 3d printing and casting.

So seismic washers are those metal stars we see on the sides of old buildings. This came out of San Francisco with the earthquake. When the old Victorian buildings started leaning, they put these stars on for support, literally washers. I was making these for my house. I had an old Victorian house. Then my house burned down. I didn’t do art for a long time after the fire. Lately I started making art that referred back to that house. I did a 3d design in plastic of those seismic star washers. We used the plastic as lost wax and burned it out. I made the stars in bronze. Most seismic washers on buildings were cast iron or steel. I cast mine in bronze as it will better fit the (house fire) narrative of the art piece.

I also have used the same process for another piece. Before my house burned, I wanted to build a shed. For the city of Denver, in order to get a permit, I had to create an elevation drawing for my shed that included all the measurements of the whole lot and my house. After the house burned down, I forgot about the drawings. Time past and then I remembered that I had these perfectly accurate specs of my old house. So I used the same process as the seismic stars and printed a 3d plastic model of my house and cast it in iron. This house being made in iron was important… its memories were locked into my family. It felt solid. It’s heavy… weighing on all of us emotionally. It is probably going to rust, which seems right. Now it’s a memory.

ANNE: What do you think about trees and wood?

WALTER: I use a lot of wood. Natural products… I really like. It all depends on what it’s for. I would get this Australian wood sold by rangers who cut out trees as fire breaks. That and collecting whatever was around, like my Ash tree dropping a branch. I really like those natural things that are there. The most important part of it was crafting it and turning it into what I want it to do. Like I did an art piece that was a hybrid of two identical items: an Irish hurling bat and a traditional African throwing knife. I was trying to combine the two cultures important to me personally. I used wood (Irish ash) and iron (Africa). Originally the hurling bat had come from it being a weapon. Now it’s a sport. A lot of things that I do, they look simple… but there is often a heavier message in it. I am more interested in the viewers narrative, but if they want to know mine, that’s fine too.

Another hybrid I’m working on is… I’m one of the artists who is making work for Denver’s 5280 Trail project. The piece is a stone model as a way-marker. The stone comes from a Colorado quarry and includes the marks that are made when stone is removed from a quarry. To me, it references the immigrants that came later to Denver. I also included the petroglyphs from the Garden of Gods, to reference who was here first. It will be placed on campus along the south end of 9th street.

ANNE: Wow.

ANNE: Are there any books, videos, podcasts, artists, etc. that have inspired you or that you are just discovering?

WALTER: The biggest inspiration I’ve had was JR Tolkien and The Hobbit.

ANNE: Thanks! I can’t wait to see the 5280 piece on campus!

Yunjin Woo: How does your work relate to the everyday? I’m thinking about your work in general with special attention to projects like One Hundred Famous Views, Invisible Labor, or Cleansing Emmanuel’s Bathroom. How do questions of labor, power, and memories come into play in your dealings with the everyday?

Anne Thulson: I wanted to do something meaningful with my life and I leaned towards narrative, metaphor and images. I was steered towards art with a capitol A. I’m sure the school guidance counselors thought, ‘Where can we put her?’ By the time I figured out that the Artworld was compromised by money, grandeur, and celebrity, I was well into my senior year of college and already accepted into an MFA program. I felt trapped but moved ahead anyway. In that program, a guest critic, Suzi Gablik, lectured. She championed art outside of Modernism and the Artworld. I remember sitting in my chair and feeling as if she was throwing me a rope and an escape map. I love her for it. I finished my degree, but with a heightened conscience and an escape plan. Since then, I discovered many artists who were pursing the same workaround. How do you make art and a living wage and work towards poetry and justice? These justice-driven poet-teachers are my community, including my colleagues at MSU Denver.

Even though I made transient, time-based art, I still wanted to make physical paintings. Why do people continue to represent what they see and think in a picture? What is a picture? Those are questions I will always love and never fully answer. I paint as a way to find out.

In One Hundred Famous Views, I painted pictures of Denver alleys because they are significant-insignificant places that people inhabit and know. Alleys are like so many acts people do every day. We pretend they don’t matter, but bit by bit, they make up most of our lives. With this in mind, I wanted to lovingly attend to them. Painting by hand is one way to lovingly attend. Brushstrokes are caresses and the body of the painter stays at an intimate proximity of the canvas while they paint. Painting is not about me making my mark or gesture or expressing myself. It is more about matching the act of painting with my act of attention with the layers of memory people bring to an alley or any mundane space. Those spaces resonate collective memory. So, on my usual walks I started photographing parts of alleys. Each painting represents a specific photo and site with odd additions like theaters and floating houses. The titles include the street names and allude to other associations as a way to acknowledge that the mundane and poetic exist together. The title of the series references One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, the 19th century prints by Hiroshige. Again, I’m interested in the notion of fame. Why do we need things to be famous? What makes a view famous? These were the last paintings I made specifically for a traditional exhibit in an art gallery. The opening and the sale of the work were not my favorite part of the process. I don’t know why, but it didn’t make any sense to me. I left the gallery soon afterwards.

Since then, I continued to read and think about painting. I came to a decision that I would still paint, but not as a professional act. I would paint as I do any non-professional practice in my life, like yoga or walking or cooking or gardening or reading fiction or being a mother. All these back-alley activities are extremely significant, but invisible on my resumé. This is when it gets interesting. Once you leave the professional realm, you are a “Sunday painter” or a “minor artist” or a “hobbyist.” I thought that was funny and I was ready to claim the titles. Still, it wasn’t exactly a great fit. I continued read and think critically about painting in a way the hobbyist doesn’t. So, I’m in a no-man’s land. There is no spot to put people who make art informed by criticism and history, but do not participate professionally in the Artworld. This seems especially true for people who make paintings, the art medium with the most capitalist baggage. What a strange place to be! Without a gallery and sales, I had to consider where the paintings as objects would go after I made them. So, I started painting even smaller canvases and I decided to give them away.

With this thinking, I made the series, Invisible Labor, with the intention to give these paintings to my children who now are grown and have walls of their own. I painted images from photographs that were significant to them. Traditional “women’s work” includes the invisible labor of archiving family memories. This is the hobbyist’s task. Within this space, I still wanted to apply an informed painting process to these very unprofessional, domestic paintings that will land on domestic walls. I was informed by the ideas of art historians Norman Bryson and Peter Geimer: various levels of the mundane, genre painting, and the question of truth in photographs. As the hobbyist, I gave these to my children. As an informed painter, I put them on my website, whose purpose is for me to start a conversation with others (like this one).

Alongside painting, I’ve maintained a post-studio practice for years. I try to do one a year. For instance, a colleague and I did performance together for a faculty exhibit at the Emmanuel Gallery. We discussed the hierarchy of our university. Who empties our trash cans every night? Who makes our photocopies? Who cleans our bathrooms? We decided to do a piece about the invisible labor in the gallery where we were exhibiting. That led to taking on the bathroom cleaning duties of the university maintenance worker during the duration of the exhibit. As I mopped the floor in that bathroom, I was suspended in an odd state between the mundane and poetic. It was a good fit.

Yunjin Woo: I would like to talk further about the politics of the strange space you occupy between the Artworld and the everyday. The same space, which is far greater than the exclusive room in which famous artists gather, is occupied by varied individuals and groups as you note—not only hobbyists but also informed artists, women, children, students, people of color, ethnic minorities, etc. Their creativity, which can be highly informed, is often dismissed, and as a result, their work occupies this liminal space between the professional art galleries and the domestic/instructional rooms. The latter is then often deemed preparatory, transitional, and thus inferior to the former. Their art may be called scribbles, decorations, or folk art. Yet, art educators are often primed to train students to aspire to the grandeur of the Artworld, which reinforces the hierarchy within the art school that closely mirrors that of the Artworld. How do you navigate this challenging paradox as an artist and educator in your work with children or students?

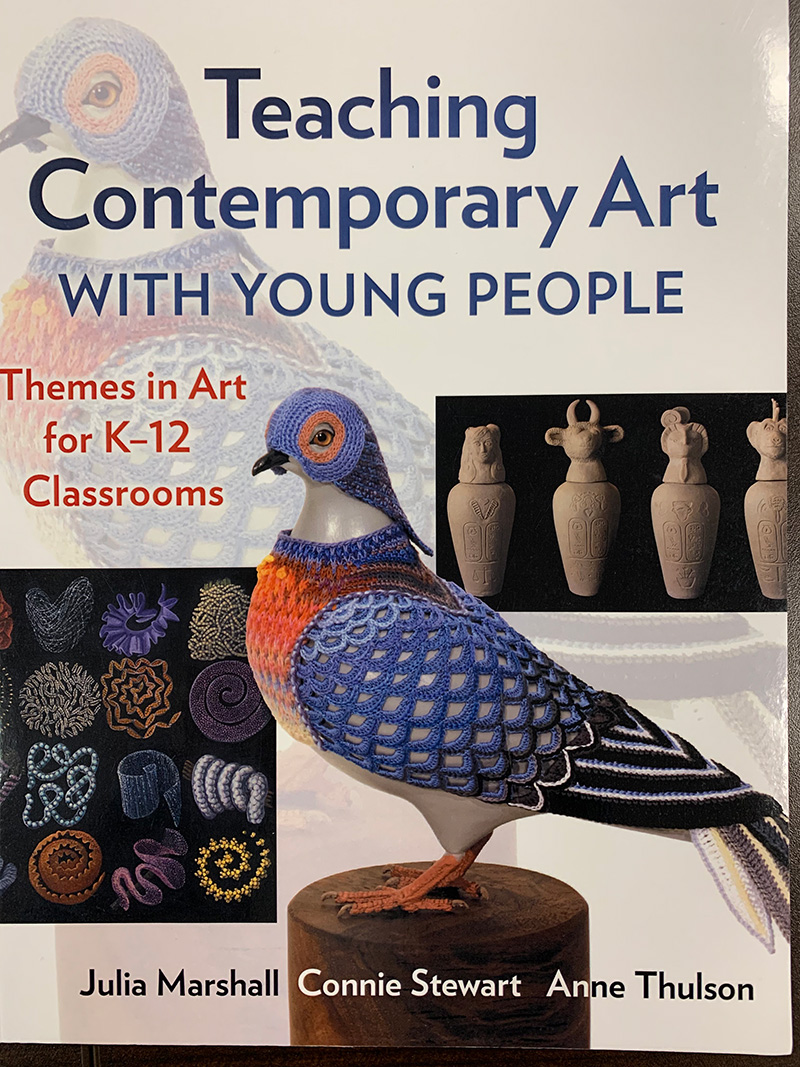

Anne Thulson: For college pre-service art teachers, I try to demythologize some things that tenaciously cling to K-12 art education: the inspired genius, modernity, the universal language of form, the limited time span of art normally used in K-12 curriculum (from 1800-1950), the Eurocentric “top forty” artists, and cultural appropriation.

Then:

When I’m teaching children, I try to create a democratic classroom where all makers and thinkers are equal and where all kinds of making and thinking exist together equally. I have them examine primary sources. I facilitate frequent conversations about ideas. I model thinking and curiosity. I try to help them make connections between poetic thinking and the everyday. After giving them lots of robust things to see and think about, I offer them prompts and/or materials for them to respond. Some of these prompts are more teacher directed and some are more student directed. I try to keep a balance. I’ve found that young children are very open to the subversive and conceptual nature of contemporary art, often more than teenagers and adults are. So, it is really wonderful to teach art to children and to work with art teachers.

MSU Denver Art students, alumni, faculty and staff are invited to submit your art stories and events so we can help spread the word on this website, in social media and via other promotions.

Let Us Know What's Happening!