Request Information

Ready to find out what MSU Denver can do for you? We’ve got you covered.

by Norman Provizer

On April 27, 1994, South Africa took a momentous step in its long walk to freedom. It was step filled with significance not only for that nation but for the wider world as well. As such, it was more than a step out of the long shadow cast by apartheid and oppression. It was also a step toward the promise of reconciliation and inclusive democracy, achieved ultimately through a negotiated “quiet revolution.”

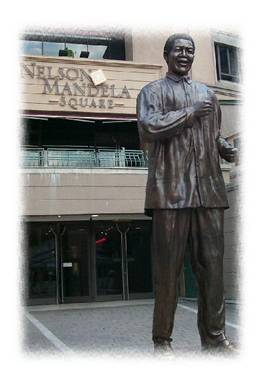

No one has come to represent this rare “quiet revolution” more than the towering figure of Nelson Mandela who spent more than a quarter of a century as a political prisoner before emerging as the first president of the new South Africa. Speaking from a balcony at the city hall in Cape Town before his inauguration, Mandela noted the sharp polarization of his society and the country’s need “to identify the values we share as a nation and respect those of others.” The search for those values was very much in mind when I attended the 2005 Cape Town International Jazz Festival courtesy of the South African Tourism.

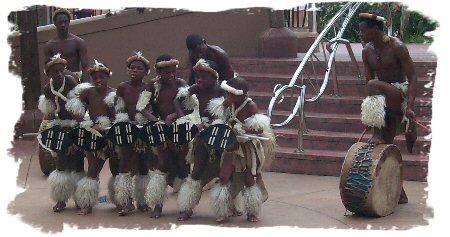

During the worst years of repression,” Mandela commented three years after his release from prison in 1990, “it was the arts that articulated the plight and democratic aspirations of our people.” In the process of that articulation, the nation developed a rich musical heritage and one deeply connected to the jazz tradition – a tradition often seen as a metaphor for liberation and freedom. As the documentary Amandla so well highlights, South Africa carried out “a revolution in four-part harmony.”

The two-day event in Cape Town brought some 20,000 people to the five venues located in the city’s impressive convention center. This was the first year that the festival was completely on its own after a five-year association with the North Sea Jazz Festival in the Netherlands. And musically, the event combined well-known jazz groups (the Dave Holland Quintet, the Yellowjackets and the Ravi Coltrane Quartet) with several less-known international players (Cuban pianist Ramon Valle, Danish saxophonist Yuri Honig, Swedish pianist Bobo Stenson and Baku-born pianist Amina Figarova) and a multitude of South African performers (representing all facets of the South African sound). For good measure, Roberta Flack and the Commodores were also on hand, serving as a reminder that musical nostalgia can, indeed, be universal.

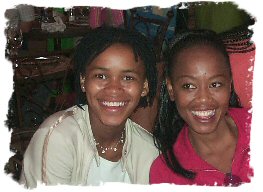

While there were many musical highlights during the two nights (especially my first exposure to Simphiwe Dana, a South African singer with the voice, songs and stage presence to become a major international star), I frequently found myself just observing the audience in the various venues. Anyone with even a passing knowledge of South Africa under the rigid separation of apartheid had to be captivated by the festival scene that included every shade of the color spectrum that characterizes this land of diversity. If you desire a picture reflecting the promise of reconciliation and inclusiveness emerging from turmoil, then nothing would do it better than a snapshot taken at the Cape Town International Jazz Festival.

Of course, that snapshot would not provide a complete portrait of a nation still in transition. Mandela called his autobiography Long Walk to Freedom and South Africa still has a long walk to take after freedom to realize the full measure of its promise. The challenges ahead, as former president Mandela strongly recognized, are daunting. Poverty in the country remains conservatively estimated at just under 50 per cent of the country’s 45,000,000 people; and the distribution of poverty there (like in the United States) reflects the legacy of oppression and discrimination. While under 5 per cent of the Whites, who make up not quite 10 per cent of the total population, fall below the poverty line, 60 per cent of the majority Black population (79 per cent of the total population) are below that line. For the category of people long categorized as Coloureds (9 per cent of the population), the poverty rate is 20 per cent. For Asians (2.5 per cent of the population), the rate is just over 5 per cent.

Along with the pressing, difficult and explosive problems concerning the distribution of wealth, land, education and housing across the racial divide, the nation also faced the disaster of HIV/AIDS and a serious wave of crime and violence in the years following the emergence of majority rule. Despite the efforts to build “a ‘rainbow nation’ at peace with itself and the world” (in Mandela’s words), conflicts among the variously colored pieces of that nation were all too real, as was the carnage generated by those conflicts that transcended any simple Black/White divide.

Still, compared to the widespread expectations of retribution and collapse, the face of the new South Africa is indeed impressive. Though critics find flaws in the prudence and gradualism mandated by the negotiated settlement of the revolution, especially in terms of economic power, there is much to be said for following a path that maintains, rather than demolishes, the nation’s imposing infrastructure – an infrastructure that represents 36 per cent of the total Gross Domestic Product generated by the entire African continent.

There are critics, as well, of South Africa’s “truth and reconciliation” approach to the crimes of apartheid, claiming that truth and reconciliation do not met the requirements of justice. But then, of course, there are always those who believe that justice must be done even if the world is destroyed in the process.

South Africa, today, stands as a world well worth saving. While attention is drawn to other parts of the globe, it is, perhaps, in South Africa that the most noble and inspiring experiment in true democracy is taking place. As even critics have pointed out, “the attainment of a liberal democratic dispensation in the land of apartheid was one of the most significant events of the twentieth century.” And the growth of that dispensation in the twenty-first century has implications and meaning for us all.

In a “Foreword” to a book marking Mandela’s 85th birthday, United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan writes, “People often ask me what difference one person can make in the face of injustice, conflict, human rights violations, mass poverty and disease. I answer by citing the courage, tenacity, dignity and magnanimity of Nelson Mandela.” Though a society is certainly much more than any individual, the sight of what courage, tenacity, dignity and magnanimity can achieve is one of the wonders of the modern world. In order to see that wonder, along with hearing some great music, moving across seven time zones, during a 17-hour flight from New York, was a small price to pay.

Norman Provizer has a Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania. He is the director of the Golda Meir Center for Political Leadership and a professor of Political Science at Metropolitan State College of Denver. Additionally, he is the jazz critic for the Rocky Mountain News, a jazz commentator on KUVO-FM (a National Public Radio station in Denver), a contributing writer for Down Beat magazine and a former columnist for Jazziz magazine. Photos by Norman Provizer.